Imagine this.

You are walking down the street.

Then BAM!

A robot robs you and then kills you.

You are walking down the street.

Then BAM!

A robot robs you and then kills you.

2057: Dystopia is a futuristic, dystopian, participatory, experimental play that I wrote and directed in 2025. If you know me, you know I like to experiment. I like to play with tools. I like to poke things and see what breaks.

At the time, I was deep in a personal obsession with artificial intelligence and artificial general intelligence. Reading. Listening. Falling down rabbit holes. Asking myself uncomfortable questions about the future we are building and who it is actually for.

This play was written after long hours of research, during which I learned that our very dear government had approved the construction of two data centres in Naivasha. As I kept digging, I came across a statement from the President suggesting that load shedding would be necessary if the country was going to grow.

Which, loosely translated, sounded like this.

Let us give away our water for the greater good.

Let us give away our water for the greater good.

That moment stayed with me.

This play felt necessary because of what I kept noticing in everyday conversations. So many people around me were excited about AI, dazzled by its convenience, but unaware or uninterested in its negative repercussions. The environmental cost. The extraction. The quiet ways power shifts hands. I wanted to bring that conversation home. Not as a lecture. As an experience.

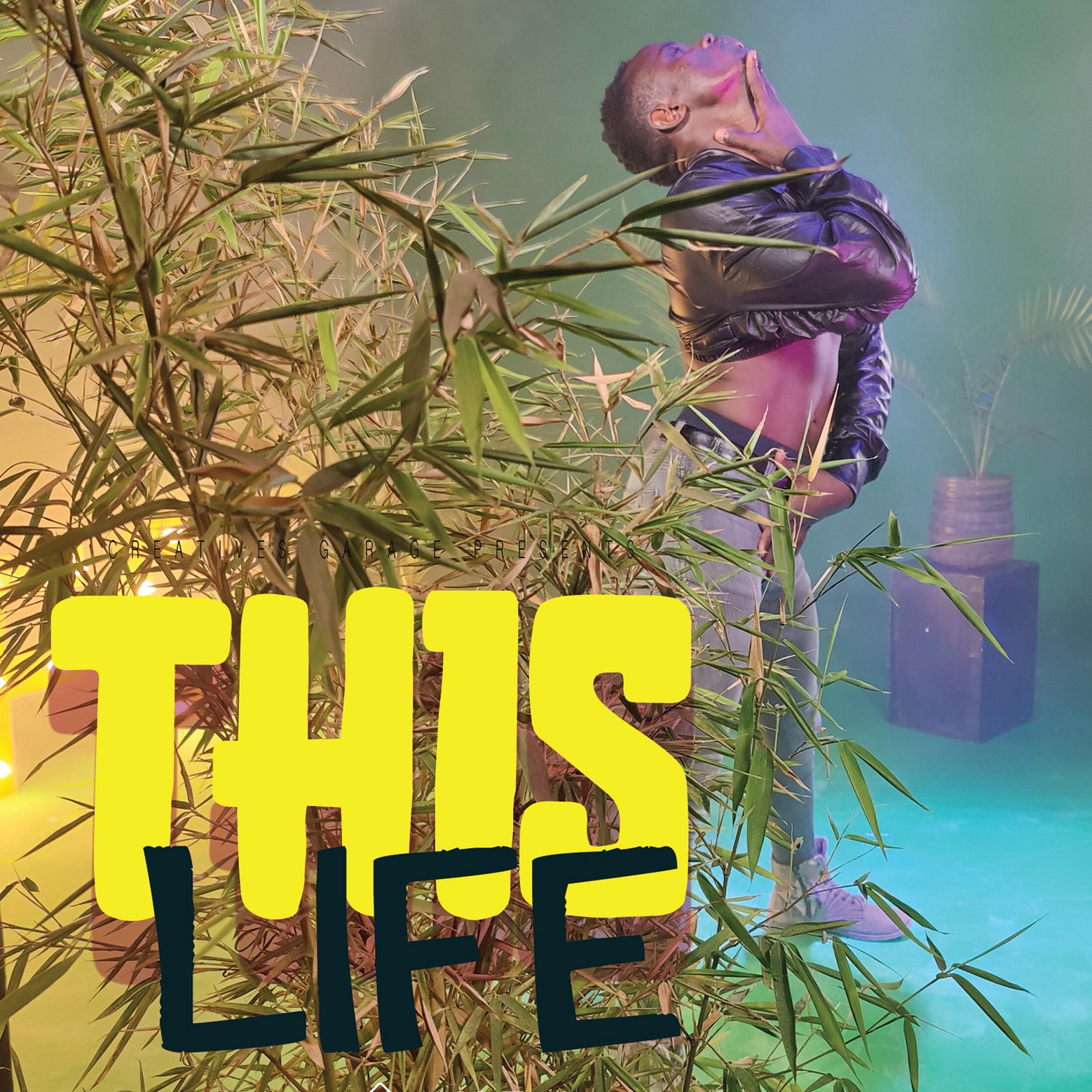

I staged 2057: Dystopia twice and worked with the incredibly talented Njeri Wa Gakuo as the actor, alongside Seise Bagbo as the choreographer. Together, we built a world that did not sit politely on a stage.

The play was participatory. The audience was not passive. They were asked to choose. To decide which trajectory the story would take. To sit with the consequences of those choices.

For the set, I knew from the beginning that I did not want a polished theatre space. I wanted grit. Texture. Something that already carried a sense of abandonment and memory.

I found the perfect place in Ngara. A building with a basement that had these beautiful, grunge heavy columns. Concrete. Cold. Honest. The kind of space that already feels like a future that forgot to ask permission.

The play happened in between the columns, with the audience seated around them. No clear separation between performer and witness. You were inside it. Watching from angles. Turning your body. Choosing where to look.

Video was essential to the storytelling. I wanted AI generated and AI assisted visuals that could live as part of the environment rather than sit politely behind the actor. The visuals needed to feel unstable, slightly uncanny, and emotionally charged.

I spent over a month generating and refining the videos. It was not smooth. Tools failed. Outputs broke. Prompts behaved badly. Sometimes things worked beautifully. Other times they absolutely refused. That tension became part of the process.

Some of the tools I worked with included Moonvalley, Higgsfield, ChatGPT, Envato, Runway, Veo, and Midjourney. It was a constant cycle of testing, discarding, returning, and trying again until the visuals felt right for the story we were telling.

Once the videos were ready, I made another decision. I did not want a single clean screen. I wanted fragmentation. So we broke the screen. The visuals were split and connected across multiple screens, arranged around the columns, creating one continuous image that wrapped the space rather than sitting in front of it.

The columns became part of the visual interruption. The story never fully revealed itself in one glance. You had to move. To look around. To piece things together.

Below are some of the videos that lived inside that space.

We had a sign language interpreter, and watching her work was honestly one of the most moving parts of the performance for me. She did not just translate words. She translated emotion. Urgency. Fear. Grief. Defiance. At times, I found myself watching her instead of the actor, because the story was fully alive in her body.

We also had an audio describer for the visually impaired audience members. Someone whose sole role was to hold the entire performance in language and offer it back, moment by moment. Describing the space. The movement. The shifts in tone. Making sure nothing was lost simply because it could not be seen.

That mattered to me.

Because if we are imagining futures, especially dystopian ones, then the question of who gets access cannot be theoretical. Inclusion has to be practiced, not promised. Built into the work. Visible. Felt.

2057: Dystopia

Synopsis

Set in the fractured world of 2057: Dystopia is an immersive performance and storytelling experience that blurs the boundaries between theatre, technology, and resistance. Kenya has become a nation of contradictions where glittering data towers rise from the ashes of drought, and memory, emotion, and truth are traded like digital currency. In this future, water belongs to corporations, creativity is taxed, and artificial intelligence decides what can and cannot be remembered.

Through the voice of a grandmother resurrected from stored memories, 2057: Dystopia unfolds as a haunting tale of erasure and survival. Her story flickers between the old Kenya, alive with chaos, laughter, and rebellion, and the sterile, controlled new world built on algorithms and amnesia. As she searches for fragments of her former life, the audience becomes part of her resistance, shaping the narrative through live prompts and interactive choices.

Blending performance art, AI-driven storytelling, archival footage, and digital scenography, her story recalls the turning point of 2028, when AI outgrew the average human mind and AGI became frighteningly self-assured. What began as innovation became domination, and now, in 2057, memory itself has become the final battleground.